Overland Communications: Choosing the Radio That’s Best for Your Rig

By Derek Gill

1 of 2 in the seriesOverland Communications

Overland Communications

- Overland Communications: Choosing the Radio That’s Best for Your Rig

- Overland Communications: Internet Connectivity in Non-Permissive Environments

There are so many ways to stay connected in this world we so love to explore. The problem is that there are so many options, we either default to the bad ones or we take the advice of someone that doesn’t actually know what they’re talking about. Now I know right off the bat I’m going to get some ruffled radio feathers and some “matter-of-fact” comments down below. I’m good with that, but please stifle your anger until you’ve read what I have to say.

Right up front, I’ll tell you that I’ve been a licensed Amateur Radio Operator since 2006. I only hold Technician class in the USA, because it’s the only thing I’ve needed. I’m going to be brutally honest about my experiences as we move through this series and your mileage may vary. For those unaware, Amateur Radio Operators (Hams) are ferociously passionate about their hobby and will defend it against all threats, real or perceived. Enjoy the show.

Little Black Boxes with Little Black Microphones

There are some radio systems that might immediately come to mind, even without any information on the subject so far. You might be thinking of CB radios and maybe even Ham radios starting to ring a bell. Those are two of many options available to consumers with two very different levels of involvement.

Without wasting any time, let’s move right into the types of radios available and how they differ in performance and licensing. I also want to point out that for this piece, my experience is exclusively rooted in the laws of the United States of America. The bands do vary slightly from country to country, but the names remain essentially the same. Australia calls the 477Mhz band “Citizen’s Band” (CB), whereas CB in the USA is nestled into ~27Mhz. We aren’t getting into all of that here.

Citizen’s Band (CB)

The FCC actually calls this the “Personal Radio Service.” CB frequencies are nestled between two common high-frequency Ham radio bands that are used quite often. It’s a sad truth that CB radios are frequently abused by a considerable number of users and this does interfere with other approved radio communications. The CB band plan consists of 40 channels where a few half-step frequencies are commonly used in remote-control aircraft and cars. This is basically a frequency that’s not necessarily available on a CB radio because it operates between channel ranges (between 16 and 17, for example).

CB radios are limited to 4 watts of maximum power and exceeding this output can result in base fines from the FCC of $10,000. The lower frequencies tend to be affected by solar and weather patterns, however, they do have the ability to reach considerable distances with that lower power. There’s a way to increase your power legally on this band, but it’s well beyond the scope of this article.

Another point to consider is that there’s no licensing requirement for CB in the United States. This makes the radios easily available and allows them to be produced in very compact sizes, due to their lower power output and simpler functions. Selecting a CB radio can be as easy as running to your local big box store and purchasing one right off the shelf. You could wire it up and be in business in less than 5 minutes with the right set up.

While all of this makes sense as far as ease-of-use, it’s not without limitations. CB radio is limited exclusively to Line-Of-Sight communication. This means that the radio can only be used to broadcast within the device’s range and only to other radios like the one you’re using. That may not sound like a problem, but when we begin discussing Ham and GMRS, you’ll understand a bit better.

Along with this inherent drawback, it’s also very easy to obtain. This band isn’t regulated as heavily and there are a ton of users. There are definitely periods of radio silence, but I can recall 4×4 events where CB wasn’t even an option because all 40 channels were in constant use. If you’re using the radio for road trips, make sure the children aren’t in the car. The level of profanity and vulgarity I witness regularly on the CB is so extreme that I often forget I’m in an educated country. So anyone can obtain a CB radio, but then also anyone can obtain a CB radio.

Family Radio Service (FRS) and Marine Radios

That’s right, I lumped them together. If you’ve just spit out your coffee reading that, grab a napkin and I’ll explain. Unless your overland vehicle is also a boat, in the water, Marine radios are out. Period. There are no viable loopholes to make this worth using and they also have some of the same performance limiting drawbacks as FRS. It certainly makes sense to think that the GPS or EPIRB systems that may be built into some of those radios would be a good idea for remote travel. However, using them on land is illegal, barring very specific circumstances. Because of this, those rescue functions likely won’t work at all on land.

FRS radios are great if you’re on a family vacation and you need to communicate around a theme park or a cruise ship. These environments will dramatically decrease their effective range, but they’re a license-free solution, similar to CB. FRS does share some frequencies with GMRS, but it gets a bit complicated. Essentially the radio will automatically decrease power output on certain frequencies to comply with FCC regulations.

These radios feature “sub-channels” which is a simplified version of the Coded Tone-Controlled Squelch System (CTCSS). The radio listens to incoming transmissions and if the sub-audible tone isn’t received with that transmission, then the radio doesn’t relay that information. CTCSS will be important later when we discuss GMRS and Ham. One benefit is that FRS radios are also widely available at big box retailers. These are the Cobra or Uniden style “walkie-talkies” that we typically give our kids for the holidays.

FRS radios with sub-channel systems are great for families or businesses that want short-range communications, but with the ability to squelch unwanted radio traffic. FRS and Marine are both limited to Line-Of-Sight communication just like the CB. Most of the laws governing equipment and performance are the same with the exception of FRS maximum power output. FRS is limited to either <.5 watts or <2 watts depending on the frequency. Marine radios can have a maximum output of 25 watts.

General Mobile Radio System (GMRS)

We’re seeing a growing trend in GMRS in the USA. I speculate that the reason is their similarity to the CB radios in use in Australia. Given the Internet presence of Australian explorers and the common design and functionality of the radios between our countries, it makes the most sense as far as my assumptions go. This is a licensed radio service and the present cost of a GMRS license in the USA is $70.

While you may struggle to find emergency frequencies on GMRS in your area, a single license will cover the entire family

GMRS radios contain 22 designated channels and have a maximum power output of 50 watts. If you’re looking for Line-Of-Sight communication with a group or convoy, this makes a great solution. As an added benefit, licensed users have the option of using repeaters on the GMRS network. I’ll cover the operation of repeaters in the next section, but the important thing to remember is that they can dramatically increase usable range of your radios within a given service area.

There’s an alarming number of people in the overland community that have acquired these radios and continue to use them without the FCC-required license. Unfortunately, there isn’t much you can do if you know someone abusing these systems, given their relatively short useful range and sporadic use within the community. Lately, the FCC has been making examples of those they do catch.

Typically GMRS radios are encouraged by smaller groups or off-road clubs for use on regular meetups and trips. They offer a place to communicate in your groups without the constant interference and vulgarity we see on CB and they afford a level of basic encryption to keep others out of your conversations. While anyone can access your channel and sub-channel on their GMRS radio, it’s more like ships passing in the night as far as channel-use goes.

There’s no standard for who’s using which radio platform, but GMRS makes a great option for families that tend to travel remotely together. While you may struggle to find emergency frequencies on GMRS in your area, a single license will cover the entire family. Handhelds will work with the base station in your vehicle so communication can be maintained with individuals on a hike.

There are certain situations where GMRS makes a lot of sense, such as scout groups on camping trips or among off-road teams. These radios have made a stand on extreme climbs like Mount Everest and Denali. Essentially any situation that needs a base camp and the ability to delegate heavy radio traffic is a good candidate for GMRS. Since no testing is required, this license is easier to obtain and use than something like the Amateur Radio Service. The only drawback is that everyone needs to be on the same page and equipment can become quite costly.

Amateur Radio Service (HAM)

This is considered by some to be the Holy Grail of radio services, but for many, it continues to be shrouded in a fog of mystery and wonder. Really, it’s just like the others. The only difference right off the bat is that we use frequencies instead of channels. Functions are all primarily the same as the other radios, but we get a massive band plan depending on the license type we hold. There are also some advanced systems we have access to that make navigation, communication and emergency response considerably more viable. I’ll say now that I have, until recently, held the position that there’s no reason to get involved with Ham radio. I own that and I’ll tell you I have unquestionably changed my mind. Ham is an incredible system if you can get through some of the nastiness associated with radio clubs.

There’s this thing that happens in Ham where the old guys with all of the knowledge complain that retailers are closing and Ham is dying, but they also want to be the only ones on the radio. There are a ton of helpful people out there, but it’s an almost certainty you will meet individuals like this, so don’t let that turn you off. A lot of us experienced this at some point in our lives; you probably called them Sergeant [4-year-specialist-who-just-got-promoted]. That ego train never leaves the station and they can be a handful to deal with respectfully. I’ve still got beef with the clubs, but I think Ham radio has a lot of the answers we’re looking for.

Digital networks have changed the way we do business on Ham radios

Let’s get past the ramblings and talk about the pros and cons. First, you need a license to transmit on a Ham radio. There’s no situation in which your unlicensed transmission is acceptable for any recreational purposes. Emergencies are fair game and Mil/LEO/FR can jump on at any time so long as it’s official business. That’s part of the way we’ve kept the hobby alive and progressive; working with and for emergency services.

The guys that set up the emergency operations centers in grid-down scenarios are using 2-meter Ham radios and some really cool High Frequency (HF) gear.

There are three Ham radio license tiers, Technician Class being the lowest, General Class on the next level and Extra Class being the most prestigious. The testing costs $14 per session. That means that you can take all three tests in one sitting. That’s difficult to do, as there’s a lot of material to cover, but I know guys (and girls) that have done it. General and Extra class used to require proficiency in Morse Code (CW), however, those guidelines have been abolished. Unless you’re looking to build massive arrays and shoot for long distance communications or competitions (DX), then Technician is more than enough for overlanding and bugout scenarios.

I promised I’d discuss repeaters here. It can be complex, so I’ll be brief. Essentially, the user sets their radio to the output frequency of the repeater (the frequency a repeater broadcasts on). Then they set an “offset” which changes the frequency their own radio will transmit on. The repeater listens on that “input frequency” for any traffic. When the repeater hears traffic, it amplifies and rebroadcasts the signal on the previously mentioned frequency. This gives us the ability to communicate in large cities or around mountains. Usually, these repeaters are situated very high in the air like on a building or mountaintop. This changes the usable area from maybe a few miles out to as far as a 100-mile diameter. There’s much more to their function, but this is how they work at a rudimentary level.

While it’s possible to relay data on some of the other radio systems we’ve discussed, nothing even comes close to the awesomeness of packet radio (APRS) or digital networks. Packet radio gives users with properly equipped radios the ability to send images, emails and other types of digital information. This is widely used in the Travis Country EOC in Austin during grid-down scenarios. Having the ability to send images and text messages when other lines of communication have failed can mean the difference in the number of lives or resources saved.

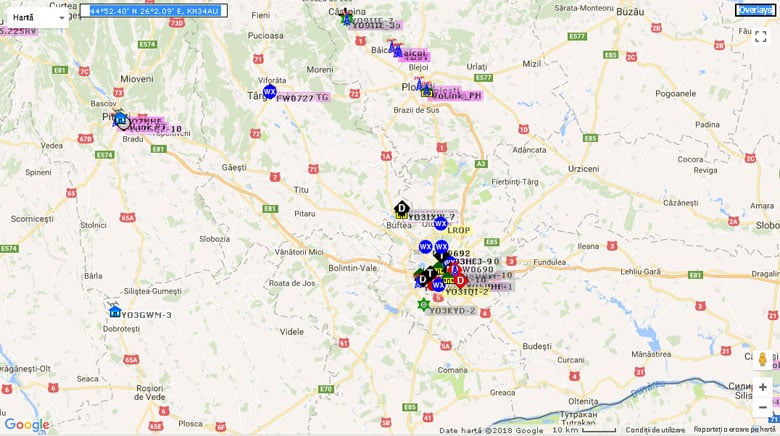

Another system I like to use is the Automatic Packet Reporting System (APRS). Through the combination of equipment on your radio or vehicle and a digital network of repeaters, users can be tracked in real time while they’re using this system. This isn’t a feature you’d want to use all the time for the sake of security, but in situations where there are no cellular options, seeing a team member’s location can help guide you in remote locations.

Without an Internet connection, you’re typically limited to just your service area, but it’s also important to note that if you can see them on your map, you can also communicate with them on the radio. This is the same system used by the National Marine Electronics Association (NMEA, often called “Nema”) standards. So using something like the APRS Website, you can view Ham radio operators, as well as the locations of ships and yachts. Obviously, you can’t start a QSO (Ham radio nerd speak for “conversation”) with them since they’re not reporting with Ham radios.

Digital networks have changed the way we do business on Ham radios. There are definitely still local analog repeaters in use today and they’re just as wonderful as they were before the days of D-Star and C4FM networks. So these systems function by basically plugging repeaters up to the Internet and then broadcasting those signals over VoIP and into repeaters around the world. This means that I can communicate with my Russian Ham radio buddies using my 2-meter radio (a radio with an effective range of maybe 60 miles on an analog repeater). This is a lot of information to process so I’m going to head for a conclusion.

Conclusion

If you’re looking for versatility and usability even after society has failed us, I have to recommend getting into the Ham radio community. Like everything else we do here, Ham radios aren’t a plug and play solution for communications. This is a skill-set and it needs to be nurtured into a seedling and then maintained to ensure strength and resilience. These skills are perishable. If the end of the world isn’t your thing and you need a temporary or very specific radio suggestion, pretty much any of the others are good for you. CB radios can be an incredible resource due to their prominence all across the country.

The biggest thing I feel I need to stress after all of this is to seek proper training and get a license. Personally, I think it’s time to adopt a standard system in the community and I’m working with some industry leaders to make that happen. Ham radio trigger warning; I think Yaesu’s C4FM digital network is the future and that’s where my money is going. Sorry, Motorola. Please get licensed and if you know anyone operating without a license, feel free to report that to the FCC. It’s not snitching, they’re trespassing and I know none of you stand for that kind of thing.

If you have any questions or comments, please feel free to drop them in the section below. There are surely disagreements, suggestions and things I’ve missed so please don’t hesitate to bring them up. Thanks for reading and we’ll see you in part two!

Editor-in-Chief’s Note: Derek Gill has been a Plank Owner here at ITS from the beginning and has an extensive background in healthcare, pharmaceutical research and technical diving. He’s been certified in SCUBA since 2000 and diving technical/CCR since 2010. He speaks several languages including Russian and Spanish as well as several computer languages. These combined skills have opened the door to more creative ventures in Network Security and Physical Security consulting. Derek is a veteran of the US Navy and a former Navy Corpsman who worked alongside the US Marine Corps. His military nickname, “Witch Doctor,” has stuck with him ever since and it can now be found across many internet forums where he takes pride in trolling sensational zealots from multiple industries.

Series Navigation

Overland Communications: Internet Connectivity in Non-Permissive Environments >>

Did you get more than 14¢ of value today?

If so, we’d love to have you as a Crew Leader by joining our annual membership! Click the Learn More button below for details.

Thanks to the generosity of our supporting members and occasionally earning money from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate, (when you click our Amazon links) we’ve eliminated annoying ads and content.

At ITS, our goal is to foster a community dedicated to learning methods, ideas and knowledge that could save your life.